Pop’s Paper Dolls: A Short History of Yé-Yé

A little more love for yé-yé, plus a record giveaway for Juniore's new album and a companion playlist to last week's "If You Like [The Sixties]" mega-recommendation post.

I’ve been procrastinating a deep dive into yé-yé for a long time now. So long, that there’s now a far better piece about it up on Reid’s Every Genre Project than I could ever have written.

Is that going to stop me, though? Well, no, not quite. I still have a record to give away and a beloved genre to gush about, so I hope you’ll indulge me in some further exploration.1

Yé-yé-yeah!

Yé-yé is quite a clever little genre because it was, in essence, artificially manufactured. You’ve surely heard of manufactured bands. Every flavor of boy band, going back all the way to The Monkees, just for a start. But an entire genre? An entire listenable genre?

That’s yé-yé. At least, that was yé-yé originally.

I don’t mean that it was a mixture of different styles, though naturally it was. Just like Reid describes, it melded “rock and jazz influences with traditional French chanson, bubblegum, exotica, and Baroque influences.” I’d go further than that, actually! Surf rock, sunshine pop, psychedelia — these were all part of the yé-yé panoply.

What I mean is that the genre was not borne out of any musician’s desire for artistic expression, but rather from record producers’ marketing interests.2

Barely of-age girls sang and danced to the music written for them by the middle-aged men who mocked and sexualized them.

Sixties French youth culture was dominated by a radio show turned magazine called Salut les copains, a sort of proto-Tiger Beat that gave rise to yé-yé’s biggest stars. These stars were generally teenage girls, all carefully chosen and styled to have a distinct marketable “type”: the bookish one, the fashionable one, the hippy, etc.

As you can imagine, style won over substance for a lot of these acts. Many of their most famous numbers were covers of English-language hits, like Sylvie Vartan’s charming (if not-so-expertly sung) rendition of “Le Loco-motion”:

Vanity and apoliticism became synonymous with yé-yé in a way that must have come across ridiculous given the increasingly progressive cultural landscape of the era.

More importantly, though we may retrospectively see female-dominated yé-yé as a kind of reaction to the male-dominated rock’n’roll of Britain and America at the time3 , the fact remains that it was an overly commercialized and exploitive industry. Barely of-age girls sang and danced to the music written for them by the middle-aged men who mocked and sexualized them.

And there was no one who got away with it more or better than Serge Gainsbourg.

Serge Gainsbourg wasn’t the only man who wrote yé-yé hits, but he’s certainly the sleaziest most well-known (though perhaps not for the sugary, coy songs of this genre).

If you know Gainsbourg, it’s likely for his preternaturally hip collaborations with It-Girls Jane Birkin and Brigitte Bardot. His best known (and raciest!) song, “Je t'aime... moi non plus,” was actually sung by both.

Gainsbourg’s lothario reputation was so extreme that the story of this particular song deserves a little diversion of its own.

You’d expect that Jane Birkin would have been the inspiration for this passionate, over-the-top track — it’s her version that soared to the top of the international charts, after all — but it’s actually Brigitte Bardot who holds that honor. In fact, she practically demanded that he write it for her.

After a particularly lackluster date, Bardot called him up and told him that there was only one way he could make it up to her: by writing the most beautiful love song he could imagine. He obliged, and they recorded it together in a session just as steamy as the more famous version you’re likely familiar with. Bardot didn’t want it released (it upset her husband, you see — how utterly French, n’est-ce pas?), but changed her tune after Birkin’s became so popular.4

Maybe you can imagine what happens when a man like this gets free reign to write songs for freshly discovered teenage pop stars.

France Gall was one of Gainsbourg’s most prominent protégés. He wrote “Laisser tomber les filles” for her, which remains an oft-covered pop classic, and her music video dramatization of the lyrics is genuinely innocent, despite the schoolgirl theme.

But as soon as she turned eighteen, Gainsbourg had something else in mind for her.

Highly risqué for 1966, “Les Sucettes” (Lollipops) featured double-entendre so flimsy that Gall’s reputation became pornographic practically overnight. At her age, she had no idea what she was truly singing — she felt betrayed by Gainsbourg, who she believed was openly mocking her, and never recovered from the career blunder.

Of course, not every yé-yé star was the result of corporate manufactured greed or sexual objectification.

As Reid says:

…some yé-yé singers like “Zou Bisou Bisou[‘s]” Gillian Hills were a sort of cog in this somewhat exploitative machine singing songs of naïveté written by men, whereas others like Françoise Hardy and Jacqueline Taïeb started in the vein of coquette, fresh-faced televised appeal but transitioned to established careers based on songwriting prowess.

Françoise Hardy is the most famous example of what yé-yé would come to be when artistry was allowed to flourish over fashion (though naturellement she was a fashion icon in her own right).

More folk than pop (and mostly writing her own music), Hardy’s talent and effortless chic inspired every rock star of her day — Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, and David Bowie all paid tribute to her in one way or another.

Taking more inspiration from The Who and The Doors than Joan Baez, Jacqueline Taïeb wove in elements of garage rock and psych to her brand of yé-yé. Her iconic “7h du Matin” (which she also sang in English) provides a stark contrast to Gainsbourg’s sexualized Lolitas: she’s just a regular teenager singing about getting ready for school, wondering which sweater to wear, and whether Paul McCartney can help her with her English exam. It sounds fresh and modern even now.

Yé-yé may have started life as a pre-fab reaction to English-language mod rock, but the cool, understated mix of genres that it developed into thanks to the women who made it their own is what keeps it relevant and respected to this day.

Yé-Yé’s Legacy

If you want to explore how yé-yé has developed since the ‘60s, there are a few roads you can follow.

The ‘90s saw a resurgence of many ‘60s sounds, but one that was most obviously informed by yé-yé was Shibuya-kei, a Japanese style similar to city pop that took its cues from lounge and soul.

Quite a lot of twee also had yé-yé to thank for its popularity, not to mention much of its fashion sense. Where would Belle and Sebastian be without it?

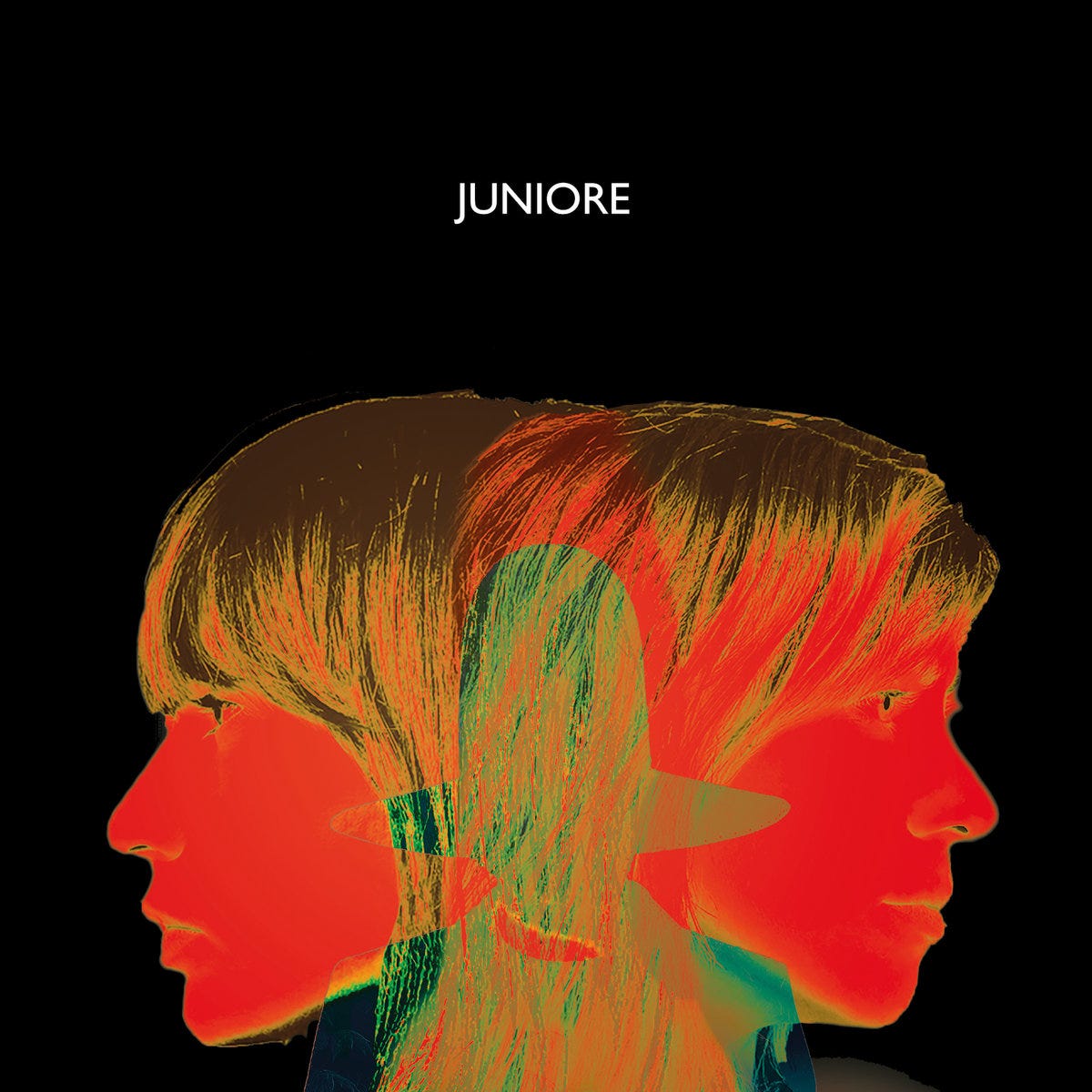

These days, there isn’t too much in the way of yé-yé lineage that isn’t outright reproduction. I’ve shared a few already last week, but I want to give a little more screen time to the best of the bunch: Juniore and their September 2024 release: Trois, Deux, Un.

Remember all of the disparate elements we’ve already discussed yé-yé bringing together back in the sixties? Chanson, surf, garage, baroque, and psychedelia, oh my!

What makes Juniore so special is how beautifully they pay homage to every one of these genres without devolving into parody. Does the addition of a little Ennio Morricone flair make it sound a bit like a Tarantino soundtrack? Sure, though I have to admit that makes it all the more appealing to me.

There’s also a bit of ‘80s does the ‘60s new wave sneaking around on tracks like “Déjà vu” reminiscent of the B-52s, which feels perfectly at home on such a danceable album.

For months now, I’ve been hanging on to a copy of this record that I want to send your way. Finally, I can share the wealth!

Below the fold: A chance to get your hands on the Juniore album, a companion playlist to last week’s If You Like [The Sixties] post, and a little bonus playlist for those who have read this far.

Did you know proper footnotes get hidden behind paywalls, even if the text that references it isn’t hidden? Silly. I don’t want the footnotes to be hidden. Here’s what they say:

1. A huge thanks to Rivers, without whom this post wouldn’t exist. Ages ago we recorded an episode of the now sadly dormant Quarantine the Past podcast on this very topic that never saw the light of day, and much of the research and music collection for this post I owe to him. Please follow him if you don’t already!

2. I mention constantly that I’m not a music historian and I’m ready to drop any argument I make at the slightest provocation, but this is pretty much the only point where I might disagree with Reid (if there’s anything to disagree on at all, really!) where he mentions that yé-yé, like so many other ‘60s musical genres, is anti-capitalistic. It may have fed off the anti-establishment genres of the times, but I get the impression that this was a money-making venture if anything, though it grew to be so much more and its influence developed quickly.

3. Or, let’s be honest, of all times.

4. They certainly weren’t the only women he shopped the song around to — Marianne Faithfull was at least one other, but she declined.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to New Bands for Old Heads to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.